Author's Notes: Like a lot of things on this web site, this article is a work in progress and will get revised as new information comes to light. Feel free to email me with any corrections or information you want to pass on. To parapharase Bones McCoy, "I am teacher, not a historian."

1921 is one of those crucial dates in Canadian football history. In that year, the number of players on a side was reduced from 14 to 12 and the concept of snapping or hiking the ball by the center was introduced. Prior to 1921, the ball was heeled back by one of the linemen instead of being snapped back with his hands.

Canadian football has its roots in rugby and in the early years, it was rugby. Over time, the game evolved and changed in Canada from the traditional rugby played in England. A lot of the details of the changes seem to have been lost or are at least awaiting rediscovery. I was initially going to ignore the pre 1921 era, but recently I came across some line-ups from that era and found them very interesting for the light they shed on how the game of footbal evolved in Canada.

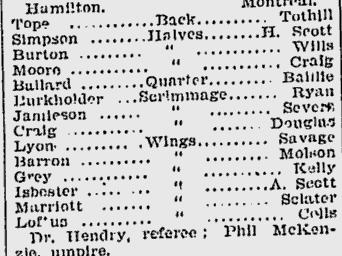

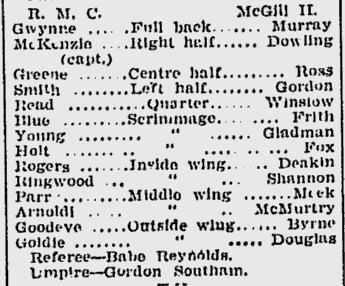

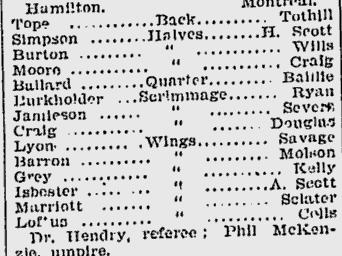

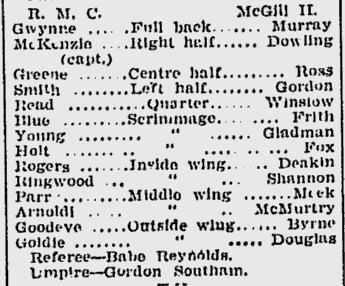

The oldest line-ups I have come across so far are from 1908, and two of them are shown below. One is from an IRFU (Interprovincial Rugby Football Union) game between the Hamilton Tigers and the Montreal Winged Wheelers and the other is an intermediate game betweeen the Royal Military College and a squad from McGill. For those not familiar with the IRFU, or the Big Fouras it was often referred to, it would go on to become the East division of the modern CFL.

The 14 players are divided into positins as follows: 1 quarter (back), 3 halves (half backs), 1 full back (or just back), 6 wings or wing backs and 3 scrimmages. The first three positions should be quite familiar to modern football fans, but the last two (wings and scrimmages) will seem odd. In the "everything old is new again" school of history, the term wing back returned to briefly to Canadian football in the 1970s to refer to a player was a combination running back & receiver. The best known player to fit that description would have been Johnny Rodgers of the Montreal Alouettes. Back in 1908, however, and for many years to follow, the term wing or wing back referred to the linemen. The second line-up shows a bit more detail of the evolutoin of names as the 6 wings are divided into three types: inside wings, middle wings and outside wings with two of each. As you will see, the term wing would in following years often be dropped, and the positons referred to simply as insides, middles and outsides. These names would eventually be displaced by more modern terms origininating in the United States, but they have a simple correespondence to the modern terms.

The one lineman position that is missing from all this is the center and that is whee the scrimmages come in. The three scrimmages who would play in the center of the line were replaced in effect by the single center who snapped the ball back in 1921.

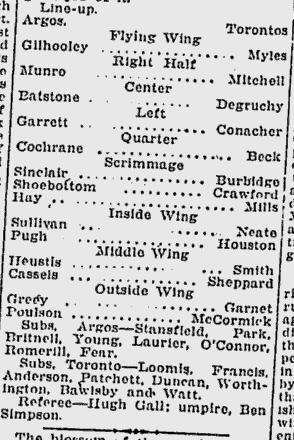

The next line-up comes from a 1920 game between the Toronto Argos and a team simply called the Torontos. You might recognize at least one name in this line-up, Lionell Conacher, who was voted Canada's top athlete for the first half of the 20th century, is at half for the Torontos.

The only real change from the 1908 line-ups comes with the first position where the term full back has been replaced by flying wing. This is somewhat ironic as the term flying wing has come and gone, bu the term full back has returned and is still with us today. The flying wing position would itself evolve over time from a running back positoin to mainly a receiver positon and eventually give way to the more modern term of flankerand then slot back. Keep in mind, however, in 1920 there was still no such thing as a forward pass.

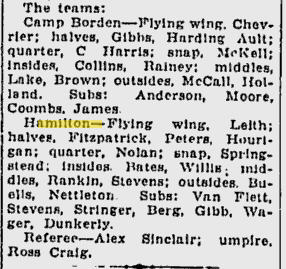

As mentioned previously, in 1921, the number of players per side was reduced from 14 to 12. The following line-up is from a 1926 game between the Camp Borden Bombers and the Hamilton Tiger-Cubs of the ORFU (Ontario Rugby Football League). The format is a bit different than the pervious examples, but is a common format used by newspaers of that time.

The one big change is the position of snap which was short for snap back which over time would become the modern center. There are some other minor changes as the prefixes center, left and right have vanished from the halves and the word wing was often dropped after the positions of insides, middles and outsides.

With the rule changes of 1921, the seven man line was established which lasts to this day on offence. An offensive team is required to have seven men on the line of scrimmage, and a semi-common penalty in a modern game is that of an illegal formation where the offense is moving receivers around and fails to have the required seven men on the line of scrimmage.

One question you might be asking yourself about the position names to this point in history, is what about defensive position names? The answer seems to be that there were no unique defensive names at this point. Players were expected to go both ways for 60 minutes and there were fairly strict rules on subsitutions in regards to how many could be made and when. If a player was injured and had to come off, he had to remain off for the rest of the quarter. The seven linemen would simply turn around and play the same positoins on defense. Remember there is still no forward passing until 1929, so teams had to move the ball either by running or kicking. The outsides (ends) were just another pair of linemen, whose main job was to block for the halves and flying wing.

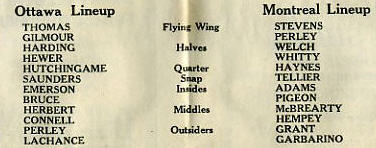

Moving forward a few years to 1931 with the passing era started there is no change in the position names. The following is a line-up from a 1931 program featuring the Montreal Winged Wheelers and the Ottawa Rough Riders.

A couple of interesting names to note in this game are Ottawa great Eddie Emerson at inside (guard) and Hawley (Huck) Welch at half for Montreal.

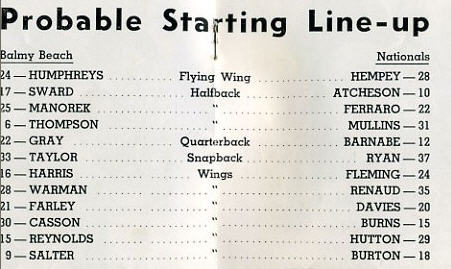

Advancing a few more years into the future, here are the line-ups from a 1938 game between the Toronto Balmy Beach squad and the Montreal Nationals of the ORFU.

Any differences are barely noticable, but the term quarrterback is starting to become more common than simply quarter. On the other hand, this program shows that the old term of wing was not quite dead, but the first two wings are the insides (guards), the next two are the middles (tackles) and the last wo are the outsides (ends). One very notable player in this game is Johnny Ferraro at halfback for the Nationals.

One thing to keep in mind when looking at old line-ups is that players were much more likely to move around between positions in those days. Many quarterbacks played halfback, players often switched between flying wing and halfback, and linemen could even turn into halfbacks or flying wings. Two of the players for Montreal in the above line-up are #20 Bill Davies and #15 Tommy Burns, listed as middles, but both often played flying wing. A lineman over 220 pounds was a rarity, and many were closer to 200 so switching to a running back position was no real problem whereas today it hard to image a 300+ pound offensive lineman as a running back except on some type of trick play.

Prior to the early to mid 1930s, Canadian football was just that....Canadian. A few Americans had ventured forth to the great white North to play football prior to this, but it wasn't an issue. The years 1935 and 1936 were crucial ones in changing that perception. What happened in 1935 was that the West in the form of the Winnipeg Blue Bombers won the first Grey Cup by a Western team, and they did it with the aid of several imports such as Fritz Hansen. The West had been challenging for the Grey Cup since 1921, and for the most part getting their butts kicked every year while being sneered at by the East football establishment and media. It wasn't that the West didn't produce good football players, but with a significantly lower population, they were just not as many of them. Add to that the fact that the West team always had to take a long train ride East to play the Grey Cup away from home, and the West didn't have much of a chance. The Regina Roughriders dominated Western football from 1928 to 1932, but went East five straight years and came back empty. Winnipeg got tired of being stomped on by the Riders and set their sights on both Regina and the Grey Cup by stocking up on imports. When the Bombers won the Grey Cup in 1935, defeating the Hamilton Tigers 18-12 right in Hamilton, the East was in shock. Promptly in 1936, the East dominated CRU (Canadian Rugby Unon) who set the rules for football in Canada, set out new rules on imports. Only players who had been resident in Canada for 12 months prior to October 1 (roughly when the season started then) would be eligible to play. The West balked at this, and in fact in 1936, the Regina Roughriders were not allowed to play for the Grey Cup because of the five imports on thei rteam - even when the Riders offered to drop the imports for the big game. After a number of years of infighting between the East and West over imports, rules were put in place to regulate what constituted an import and how many a team could have. The modifications to those rules over the years has been an important part of Canadian football.

The above might have seemed like a diversion from the topic of this article, but here is the point. American influence on Canadian football was increasing and as American players and coaches came North, they brought American terminology for the positions with them. World War II might have slowed things down a bit, but by the 1950s, Canadian football was increasingly being turned over to Americans. The Toronto Argonauts with their three straight Grey Cups from 1945-47 with an All-Canadian line-up was probably the last bastion of the Canadian in football in this country. Everyone else was using imports and eventually the Argonauts would too. The 1950s saw the steady import of American coaches such as Doug (Peahead) Walker in Montreal. As American players became more important to the success of Canadian teams, the ability to recruit them also became more important, and that required connections South among the college ranks. This led to an increasing number of American General Managers on Canadian teams.

You can see the influence of the States on position names in the following line-up from a 1937 game between the Montreal Indians and St. Mary's College (San Antonio, Texas). The Indians were one of a number of short lived Montreal teams between 1935 when the Winged Wheelers folded and 1946 when the Montreal Alouettes were founded.

The games as you will notice by the 11 starters was played under American rules. You can see the American terminology for the line positions: ends, tackles and guards as well as fullback which had largely disapeared from the Canadian vocabulary over the years. As the 1940s marched on, the American terms would eventually take over. By the way, the "missing position" when comparing Amercian and Canadian football at this time was the flying wing. When American coaches started taking over Canadian teams, they obviously had no experience with the flying wing and didn't know what to do with this 12th man who didn't fit into the offensive schemes they tried to bring North with them.

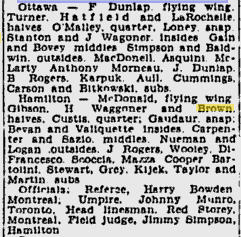

Still, having said that, a roster in the early 1950s, looks very much like one from the 1930s. Take the following rosters from a game between the Ottawa Rough Riders and the Hamilton Tiger-Cats from 1951.

This line-up was chosen pretty much at random from the early 1950s, but you can't look at it without noticing some great names in Canadian Football. On Ottawa there is Don Loney playing snap (still not called center), and a future General Managers of the Riders in Jake Dunlap. On Hamilton's roster is Ralph Sazio who would go on to coach and be GM of the Tiger-Cats and also future CFL Commishioner Jake Gaudaur. Not to be outdone, the officials for the game are all former CFL stars, Jimmy Simpson of Hamilton, Johnny Munro from the Argos and the legendary Red Storey.

There were a couple of trends happening in Canadian football in the 1950s that fed into each other. These were the developemnt of separate, specialized offensive and defensive platoons and an increasing reliance on the forward pass.

The rosters at the time were just barely large enough to support a platoon system. If you count up the players for the 1951 game above, you will see teams could dress 24 players. As the 1950s progressed, the trend towards separate offensive and defensive teams continued. By the end of the decade, it was unusual to see a player play offence and defence in the same game. It was still not unusual for players to be switched from offence to defence or vice a versa during a season or between seasons due to injuries or a surplus of talent at one position, but the days of a man playing sixty minutes were over.

Part of the reason for the platoon system can be found in the rise of the forward pass. With no passing, the quarterback was just one more guy who could run the ball, but now the quarterback needed the specialized skill of throwing a football acurately and far. It also didn't take teams long to realize how important the quarterback now was to their offence, and risking an injury to him while playing defence was not such a good idea. Still, the backup quarterback could often be found playing defensive back and even such greats as Ron Lancaster and Kenny Ploen had stints on defense during their careers.

There was also a change in the skills needed by the outsides / ends. When there was no forward passing, the ends were just another pair of blockers on the line for the backs, but now they had to be smaller, faster and with better hands to catch passes. If you still had a offensive end playing defense, it was more likely to be as a defensive back. A classic example of this would be Harold (Hal) Patterson who was an All-Star at end and at defensive back.

Into the 1940s, teams were still using a seven man defensive line, with the offensive line just switching to play defense. An increase in passing required more players to defend against it and the defensive line dropped to six players from seven. As the 1950s started, a common defensive formation would have been 6-3-3. The defensive line consisted of two ends, two tackles and two guards. With the rise of the platoon system, the terms defensive guard, defensive tackle and defensive end was created to distinguish between offense and defense, though most players were still going both ways at the start of the decade. An outstanding example of such a two way player would be John Barrow who won East Division All-Stars at both Offensive and Defensive Tackle in 1957, 1958, 1959 and 1960. After 1960, Barrow played almost totally on defense, winning another seven defensivel lineman All-Stars in the 1960s.

The term linebacker emerged with the rise of specialized defensive squads with most teams using three (the second 3 in the 6-3-3), an inside linebacker and two outside linebackers. The term inside linebacker would eventually give way to middle linebacker.

The final three players on defense were generally known as halfbacks, though again the adjective defensive was more commonly being added.

One good source of information on the changes of position names is the All-Star teams through the years. By 1962, when the first CFL All-Stars were picked (previously there had been just East and West All-Stars), the defensive line had shrunk to 5 from 6, and the most common defensive formation was a 5-4-3 or 5 linemen, 4 linebackers and 3 defensive backs. The defensive line consisted now of two defensive ends, two defensive tackles and one middle guard. Teams used four linebackers, two inside and two outside. The two outside linebackers were often referred to as corner linebackers which can cause a bit of confusion when looking at old line-ups. As you might guess, the corner linebacker position migrated into a defensive back position and the name changed to the modern cornerback.

The 1964 CFL All-Stars reflect the next stage in the evolution of defensive formations with a 4-3-5 which has remained the most common formation until this day. Two defensive ends, two defensive tackles, three linebackers, and five defensive backs. The term middle linebacker was now quite common and perhaps best epitomized by Calgary's Wayne Harris. The five defensive backs started to become further specialized into two cornerbacks, two halfbacks, and a safety. Similar changes were taking place South of the border, and it was the safety that emerged in our mentality as being the "extra" player on defence. This terminology can sometimes be confusing when comparing the American and Canadian games as in the States, they use the term safety to refer to what we call halfbacks. Someone who played safety in American college football is likely to be a halfback in Canada. Perhaps to help distinguish between the two uses of the term, the adjective free is often attached to the 12th defensive player in Canada and he becomes the free safety.

Since 1921, one thing that has remained constant in Canadian football is the seven men required on the offensive line for every play. By the end of the 1950s, though, the American terms of center, guard, tackle and end had replaced the older terms of snap, inside, middle and outside. As the platoon sytem spread, the adjective offensive was commonly added.

The two end positions on offensive naturally enough were called offensive ends and in the 1960s, they became more specialized with the terms tight end and split end emerging. This is refelcted in the CFL All-Stars for the first time in 1969 with Herm Harrison of Calgary as the tight end and Margene Adkins of Ottawa as the split end. The official positions names for the CFL All-Stars often lagged reality by a few years as the terms had been used widely in the 1960s to distinguish between the two end positions. The tight end was originally more of a blocking end, while the split end was more of a receiver. It was the emergance of players like Tony Gabriel and Peter Dalla Riva in the early 1970s that showed that the tight end could be an important part of a passing offense.

In the backfield, besides the quarterback, teams in the 1960s were using three running backs which had become the generic term for anyone who ran with the ball. The running backs were most often divided into two halfbacks and one fullback as the latter term came back into common usage from the States. The fullback was the power runner and the halfbacks were the smaller, faster guys used more for sweeps and as receivers. Unlike today where the fullback position has degraded to an almost exclusively blockng role, the fullback in the 1950s and 1960s was often the primary running back. In the 1950s, Normie Kwong typified the fullback and in the 1960s it would be George Reed of Saskatchewan.

The 12th man on offense had traditioanlly been the flying wing, but that term gave way in the early 1960s to flanker. The change in terminology reflected the change in the role of the position. The flying wing had been as much (if not more) a ball carrier than a receiver, but with the increased emphasis on the passing game, the flanker became almost exclusively a receiver. You can see the shift in the stats and in the CFL All-Stars. In 1962, when the CFL All-Stars were first introduced, they actually list four running backs and neither the term flanker or flying wing is used. Of the four, three would clearly be considered running backs in Earl Lunsford, George Dixon and Leo Lewis while the fourth man, Ray Purdin, was listed as a running back, but better fit the ermerging flanker role. Purdin finished only seventh in the West in rushing (Lunsford was 2nd and Lewis 4th) with 809 yards, but he was also eighth in receptions with 34 and another 771 yards. Ther term flanker first shows up in the CFL All-Stars two years later in 1964 when Tommy Grant got the nod. In that year, Grant had only 2 carries and had 48 catches which was second best in the East.

Despite the increased emphasis on passing, teams in the 1960s were still running the ball more than half the time, compared to about a third of the time today. Consider the 1964 West as an example. Edmonton and Winnipeg carried the ball the least number of times at 469 and BC the most at 566. By comparison, Winnipeg threw the most passes with 356, so the the team that ran the ball the least still ran the ball 57% of the time. Calgary who ran the ball 554 times to 328 passes ran the ball 63% of the time which is close to double of a modern CFL team.

Without spending the time to do a detailed analysis of every season (a future project?), things started to change significantly in 1968. The place was Calgary and the quarterback was Peter Liske. The Stamps threw the ball 524 times to 355 rushing attempts which works out to running the ball only 40% of the time which is not far off the average for teams today. It took the rest of the CFL a while to catch on, and even Calgary backslid a bit in the following year when Liske left for the States, but the CFL had entered into a new era where teams passed more than they ran. Asa result, you didn't need as many running backs and by the early to mid 1970s, most teams were down to two running backs. There were a few years of transition where the "third" running back operated in a hybrid like position that was pretty much equally split betweeen ball carrying and receiving. These were the so called wing backs with players like Johnny Rodgers of Montreal or Tom Campana of Saskatchewan being typical. Consider some stats for Rodgers. In 1974, Rodgers ran the ball 87 times and caught 60 passes while in 1976 he had only 20 carries to 45 catches.

Once the Canadian game had made the transitoin to two running backs and four receivers, a somewhat odd change happened. The two receivers playing off the line (flanker and wing bank) were generally smaller and faster receivers compared to the two receivers on the line (tight end and split end), especially when compared to the big tight ends. What happened next was pretty much a reversal of those two roles. The small, speedy guys moved up to the line and the bigger guys moved back off the line. A new term was coined for the big, off-the-line receivers as they were called slotbacks. The terms tight end and split end pretty much disapeared in favour of a more generic term of wide receiver. The All-Star positions are a bit of a mess during the transition period with the term wide receiverstarting in 1974, then one slotback in 1978 and finally settling down in 1981 to two slotbacks and two wide recievers, and with the term tight end ending in 1980.

In recent years, there has been one more change in the position terminology for receivers. The term wide outs has largely displaced wide receiver to describe the two receivers on the line of scrimmage. Often the terms short side wideoutand and far side wideoutare used to further distinguish the two receivers. The short side wideout lines up on the side closest to the sidelines and the far side wideout on the side farthest from the line of scrimmage. There has also become less of a distinction between the type of player teams use at slotback or wideout and it is not unusual to see a receiver move from one position to the other though the type of player who in the 1970s would have been a tight end is almost always going to be lined up as a slot back. Andy Fantuz of Saskatchewan and Ben Cahool of Montreal would be good modern examples of this. On the other hand, you also have many smaller, faster players at slotback such as Geroy Simon and Weston Dressler.\

There have been a few recent tweaks to terminology in Canadian football Teams are using five and six receiver sets now as much as the "standard" two running backs / four receiver set used from about 1975 on. When there are two running backs on the field, one is generally called a full back, but the role of the full back has deteriorated to little more than a blocking back to provide protection for the quarterback or for the other running back. The second running back now is normally referred to as the tailback or sometiems the feature back, since he is the once who gets to carry the ball. Even then, a tailback that can't help out with the blocking is probably not going to last too long in the modern CFL.

The term tight end has made sort of a comeback after rarely being heard for about 20 years from 1980 to 2000. Some where in the early 2000s, Toronto started using a jumo packageor a double tight end package and all the other teams seem to have adopted it. Aas the name suggests, it uses two large tight ends, mainly for blocking. Generally, the double tight ends are extra offensive linemen, defensive linemen or fullbacks. One of the options with the package is to run a trick play and slip one of the big tight ends out to catch the ball as happened with Marc Parenteau in the 2010 Grey Cup for the Riders. It is a far cry from the hey day of the tight ends in the early 1970s.

Defensively, there have been a few minor tweaks in naming as well in recent years. The term rush endhas come into common usage to describe one of the two defensive ends, whose job is almost exclusively to rush the quarterback. Often the rush end is smaller anf faster than traditional defensive ends and would likely have been a linebacker in the NFL. Cameron Wake who terrorized quarterbacks for a couple of seasons in the CFL would be a good excample. When he went back to the States, he became a linebacker in the NFL.

Two new terms have also sprung up to descirbe the outside linebackers. They are often called the strong side linebacker and the weak side linebacker, depending on whether they player the side farthest or closest to the sidelines. More and more these outside linebackers are converted defensive backs since they are being called on the cover receivers or spedy running backs on passing patterns. Their greater speed also makes them very useful for putting pressure on the quarterback "off the edge". A downside to the change, however, seems to be increased suceptibility to the running game. If the offence can get a block fomr an offensive lineman or a fullback on the little outside linebackers, then that can spring the tailback for a big gain.